ONE DOZEN AND TWO ESSAYS

On Being Good

“Be good my child and let those who will be clever”

There is something about this saying that has always grated against my basic instincts. I have heard it quoted on various occasions throughout the course of my life and now, with the perspective of old age, I believe I have finally come to a decision in its regard.

In my humble opinion the words “good” and “clever,” should be switched. If you are sufficiently clever you will realize that being good is distinctly to your advantage. In other words, it’s clever to be good and it’s good to be clever. I am, of course, using the word “clever” as a synonym for “smart” or “intelligent.” Those are the broad terms, and they include being good within their scope.

Human beings did not become the dominant species on planet Earth by being good, they did it by being clever. “Good” and “evil” are terms which only apply within the realm of human civilization. Civilization is a bit of cleverness devised by human beings to increase the probability of their survival. Thus, anything that aids civilization is “good” and anything that harms civilization is “evil.” To apply these terms to Mother Nature is inappropriate — an anthropomorphism. She simply does not operate in that manner, survival of the fittest is her mode.

In the past, and right up to the present, morals and ethics (being good) have often been taught to our youth as something for which they will receive reward or punishment depending on their degree of adherence to the cultural mores. The reward or punishment will be administered here on Earth or, should they escape that, in a heaven or hell thereafter. This is short sighted and a disservice to the young — an insult to their intelligence. Many of them will see through it far too easily and be left without a moral compass. It is much better to teach them morals and ethics as pragmatic and the result of intelligent deliberation by their peers. An appeal to their intelligence is more effective and permanent than threat of punishment or promise of reward. When an individual develops a personal precept that runs counter to the mores of their particular culture and he or she is forced to abandon actions based on that precept by the threat of punishment, most likely the precept will still be retained.

“A person convinced against his will is of the same opinion still.”

However, if they are persuaded to abandon their precept by an appeal to their intelligence then they are truly changed. I believe the best moral guide for civilization is The Golden Rule.

There is another aspect of the saying at the beginning of this essay that I find odious. I suspect it has served as a sop to dissuade some people, primarily women, from attempting to be clever. Those with the traditional dominate position, primarily men, did not want to be challenged by those whom they felt should remain subservient. Considerable progress has been made recently in the West at overcoming this basic male insecurity. There remains some residual, but it is increasingly subtle. However, it is still glaringly obvious in other regions of the world, particularly in the Middle East. In Saudi Arabia even allowing a women to drive a car is somehow seen as a threat to male supremacy. Any society that systematically suppresses the intellectual expression of half their people is its own worst enemy.

“Be clever my child and let those who will be good”

Robert L. Mason

Mendocino, California

2011

A Modern Empirical “Religion”

I have wondered for quite some time why there isn’t a present day religion centered on the Sun. There were some examples of such in ancient times. The Romans had “Apollo,” the Egyptian gods included “Ra,” but except for a brief period during the reign of the Pharaoh Akhenaton, these were minor members of an extended pantheon. In modern parlance the term “Sun worshipper” usually doesn’t mean anything more than someone who likes to get a tan.

The Sun as the central entity of a religion would seem to have distinct advantages over the dieties of other religions. No one is going to give you an argument, for instance, that the Sun doesn’t exist. You would be hard pressed to find that kind of unanimity for any other religious figure. In addition, a very strong case can be made that the Sun is the single most important physical fact of our existence. We owe it all to the Sun — all life on Earth, all of Earth’s energy reserves, Earth itself. It would seem that anything that important is deserving of respect and maybe even reverence.

Why is it that the Sun attracts so little reverence today? The deities of various other religions whose existence and influence are at least debatable, are treated with great reverence by large numbers of people. But the Sun, whose existence no one denies and which has direct bearing on our very being, is taken for granted. I guess the answer lies in the fact that it is so integrated into our lives, so manifestly part of our existence and so constant, it doesn’t attract much attention. It’s just part of the background noise. In addition, the dieties of other religions are usually represented as something approximately in our image and it is difficult to think of the Sun that way.

Certainly, there is no denying the fact that when, on an otherwise gloomy or overcast day, the Sun suddenly breaks through and lights up the world your mood is also elevated. And it’s not just us human beings, the birds start to sing, flowers turn on their stalks and face it, and the cat moves to a sunny spot to continue it’s catnap.

One could argue that stars like the Sun are living things. Like flowering plants they originate as a seeds and grow by collecting materials or nutrients from their environment. They “blossom” upon reaching a certain size and maturity and “blow” at the end of their life cycle scattering “seeds” that will become the genesis of the next generation.

Many religions claim their deity is omnipotent, omnipresent, benevolent, and personal. The Sun is very powerful, but not omnipotent. The Sun’s range of influence is extensive, but it is, for the most part, finite. It is benevolent in a general way because it sustains life. However, it is not personal, and cannot be expected to intercede on behalf of an individual, or take sides in a confrontation. The Sun is, of course, a star and there are countless other stars. What kind of reverence should be accorded to such an entity?

The Sun is our home star. We were all born here. The Sun provides for us. It shelters and sustains us. It may be that the Sun is just part of the scheme of some more grandiose deity who is beyond the reach of our senses. It is impossible to know. But you can know the Sun. It is tangible. You can feel it. You know the feeling. . . it’s warm, pleasant, familiar. . . . like home.

The Solar System is our place in the Universe, the hearth of the Sun. Earth is the home star homestead. Therefore, reverence of the type associated with hearth and home would seem appropriate, but scaled up considerably. I believe the time is right for a new creed. One that is empirical, scientifically based and reflects our newly acquired knowledge of the Universe with our place in it.

What might devotees of such a creed call themselves? How about “Solarians.”

Knowledge as Wealth

Knowledge is a subject about subjects, a kind of metasubject if you will, and it is a difficult subject to write about without resorting to platitudes. However, platitudes become platitudes because they are generally perceived as containing a large element of truth and hence are repeated ad nauseam. Having said that, off I go.

First, it seems to me, that the more you know about a subject the more interesting that subject becomes to you. Even if it is a subject that you are not fond of, once you have penetrated it in depth, every time you encounter it again you can place that new experience in a previously established frame of reference and gain a certain amount of satisfaction in doing so. Secondly, it stands to reason, by extension, that the more subjects for which you have a substantial frame of reference, the more interesting and satisfying your life will become. Finally, there seems to be some evidence that the broader and deeper your interests in life, the longer you live. Maybe, life long learning should be thought of as prevention for dying of boredom. Boredom can kill you in any number of ways.

Most of us get our first experience in detailed examination of a subject while in school. There we are required to learn a subject in order to graduate. Unfortunately, many people quit the process once it is no longer required. Probably the greatest benefit one can get from schooling is to learn to learn, but, alas, that lesson often goes unlearned.

There is a certain amount of inertia to overcome when setting your mind to a new task. It is much easier to just continue on in a field you have already mastered, especially when it provides you with a good living, and “a rolling stone gathers no moss” (the original meaning is intended). Your chosen field of expertise becomes so established that operating within it is almost automatic and increases in your financial wealth provide you with a sense of accomplishment. However, from a knowledge point of view, it can be the difference between ten years of experience and one year of experience ten times.

Tackling a new field of learning creates new synaptic connections in your brain. These connections hook up to already established frames of reference and enable synthesis to take place. One finds that concepts and procedures learned in one field can apply in some new endeavor and provide one with insights more one-dimensional individuals may have overlooked. Often what emerges from such crossbreeding is a concept superior to either progenitor. A parallel for this exists in biology and is known as hybrid vigor.

Today’s considerable emphasis on being physically fit probably exists because one can quickly assess that kind of fitness at a glance in a right-brained manner. Mental fitness cannot be determined quite so quickly and usually requires a left-brained approach such as an extended conversation. Both types of fitness are important and both can suffer from disuse. In addition there is some overlap between them, but as the ancient Greeks used to say “The body is the temple of the mind,” and I believe that places the priorities correctly.

As indicated above, with the increasing complexity and the accelerating pace of life in these modern times, it is sometimes easier, because of mental inertia and time restraints, to become specialized as opposed to approaching life on a broad front. This is especially true when that specialty is lucrative. Consequently, many people are continually skipping across the surface of life, hurrying to the other side, and rarely take the time to find out how deep the water is at different locations. In that metaphor the “other side” represents financial wealth that for some is the be all and end all of life. The bright side of this picture is that financial success brings with it an opportunity for early withdrawal from the rat race, hopefully before you become more rat than human. Financial wealth is, however, fairly easy to lose, whereas a wealth of knowledge never leaves you entirely—short of dementia.

Each of us is in possession of a single copy of the most magnificent creation that has ever come to the attention of humanity. The human mind is the end product of three and a half billion years of evolution. It is the grandest structure in the Universe as far as we know. Here on Earth, it sets us apart from all other forms of life. It is Mother Nature’s masterpiece. It behooves each of us to make the best use we can of such a valuable asset.

When we gather knowledge of the Universe outside our head we create a simulation of the Universe inside our head. This simulation helps us to understand the context of our lives and is most easily achieved by leading a multifaceted existence. The human brain has remarkable ability to collect information (data) via the senses, test this information for consistency (truth), and store it away in frames of reference (subjects). The sum total of this subject inventory (knowledge), with all its interconnections is the simulation of the Universe that every individual creates for his or her self. Naturally, the greater the body of knowledge one possesses, the better one understands one’s existence. At some point, something akin to wisdom or enlightenment may even be achieved. This would appear to a worthy goal for the magnificent brain with which we are all blessed. Then, in your old age, you can wander through the mansion of your mind and know you are wealthy.

R. L. Mason

Mendocino, California

2008

The Philosophical Roots of Science

The word “science” comes from the Latin scientia “knowledge,” but in its modern English usage it has come to mean more than that. Also implied is a system or method based on observation. Here is my definition:

Science is an empirically based system for the acquisition, compilation and dissemination of knowledge about the physical Universe.

Inclusion of the word “empirical” denotes observations acquired by the senses. The branch of philosophy dealing with this is known as epistemology. What follows is a description of a particular epistemology, the one that makes the most sense to me:

First, a basic assumption: all objective knowledge, or any thought that carries intelligence, can be put in the form of statements. It can be communicated, or lifted from one individual’s brain, put into words and transmitted to another’s brain orally, or in writing. And this is possible regardless of truth or falsehood, how you got it, or where it came from.

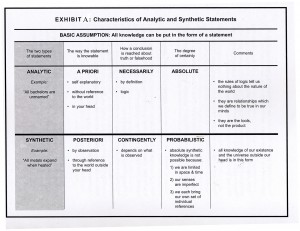

With all objective knowledge or intelligence in the form of statements, we can examine their structural content. We can do some sorting and pigeonholing. The first distinction to be made is between analytic and synthetic statements:

An analytic statement is knowable (either true or false) without reference to the world. You know it in your head (a priori) and no observation is necessary.

Example: All brothers are male siblings.

We know this statement is true because the definition of brothers is male siblings. It is true by definition. You could take the words “male siblings” out of the statement and plug in “brothers” and the statement would read: all brothers are brothers. We can tell this is true simply from the structure of the statement itself. There is no need to go out and look at brothers. It doesn’t tell you anything about the nature of brothers. Another name for such a statement is a tautology. Some tautologies are quite famous.

Example: What will be will be.

At first, this sounds like a profound statement, as if it were telling you some basic truth about the nature of reality. In fact, it is true, absolutely true, but its truth comes from the structure of the statement not from some long, hard-earned experience with the world.

The truth (or falsehood) of tautologies and all other analytic statements is necessarily absolute; they are set up by us to be so. They are true by definition but they do not address the nature of reality.

Synthetic statements, on the other hand, do speak of the nature of the world outside your head.

Example: It is raining.

We don’t automatically know a priori the truth or falsehood of that statement. Its’ truth or falsehood is contingent upon whether, in fact, it is raining and that determination requires a verification process. we must go to the window and look out, or we must listen for the sound of rain on the roof, or we must feel the dampness in the air. In other words, we must gather sense data from the world in order to confirm or deny the statement and only then (posteriori) can we determine its truth or falsehood. Moreover, such a determination is not absolute as it is with analytic statements. Sense data is fallible and not every observation necessary for a determination can always be made. If it is night, going to the window and looking out may not help. The sound we thought was rain on the roof might, in fact, just be some dry leaves blowing about, and the dampness in the air may come from the kettle on the stove.

Consequently, the determination of the truth or falsehood of a synthetic statement must always be expressed as a probability. The truth of a synthetic statement may be very highly probable.

Example: Gravity exists.

But since every possible observation has not been made (and never will be) the existence of gravity must remain very highly probable, but not absolute.

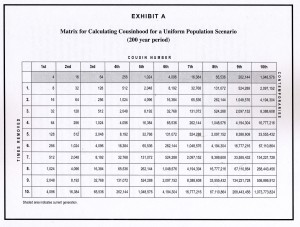

On the other hand, even though the truth or falsehood of synthetic statements cannot be determined absolutely, they do tell you something about the world. They are useful in dealing with reality. Exhibit A lists the characteristics of analytic and synthetic statements and displays them in summary form.

(click on image for larger view)

Since it is very highly probable we human beings exist, and since it is also very highly probable the world, nature, and the universe also are a reality, it is important that we develop a system for determining the relative truth (or falsehood) of synthetic statements, a kind of test of their reliability. In fact, we have done just that and we couldn’t have succeeded in nature to the degree we have if such a process had not become a manifest part of the human experience.

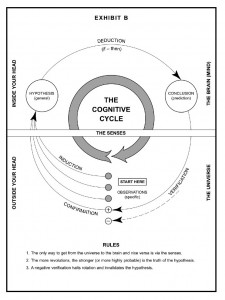

How do we arrive at important synthetic statements in the first place? There is a process labeled induction by enumeration which begins with observations of reality. Initially, this is a random process, but eventually observations start to lump themselves together into categories and frames of reference.

For example, I see an animal. Eventually I see another that looks like the first, and then I see a third and a fourth. These observations become a frame of reference centered on that kind of animal. I give it a label, “cat.” I notice the first four cats all had tails. I see a fifth and a sixth cat. They have tails too. And now I make an inference. Based on my specific observations, I make a generalized statement about cats:

Example: All cats have tails.

This kind of synthetic statement is called a hypothesis, and the process is induction by enumeration or inductive logic. Inductive logic always moves from the specific to the general and is synthetic in nature. Having made the hypothesis, I now treat it as true. But if I am realistic, I realize its truth is only probable to a degree, and that degree is tied directly to the number of observations I have made (namely six). However, I proceed merrily along as if the hypothesis were true. I make a prediction. I conclude that the next cat I see will have a tail. This is deductive logic. Deductive logic always moves from the general to the specific. I see a seventh cat. It has a tail. This observation confirms my hypothesis and my confidence level rises. I continue on in this manner growing more and more confident until— oh no!— a cat without a tail! Woe is me! But all is not lost. I really do not need to start all over at the beginning. My observations are still good; it’s just my hypothesis that is flawed. It needs a little work. How about this:

Example: Most cats have tails.

This process of moving from the specific to the general, from the general to the specific and back around again is the cognitive cycle and is the basis for what is known as the Scientific Method. Scientists call hypotheses that are very highly probable facts. But even facts are not held to be absolute. A diagram of the process is shown in Exhibit B.

(click on image for larger view)

We think this way naturally, without making a conscious effort. The Scientific Method is simply an elaborate formalization of the way our heads work automatically. I would go as far as to say any intelligence that gathers knowledge of the Universe empirically (through the use of senses) would necessarily function in the same way.

Exhibit B is a fairly good representation of the cognitive cycle, with one shortcoming. It shows the realm inside your head (the brain) as isolated and separate from the universe outside. When, in fact, you and your brain are in the Universe as well. Thus we are able to make observations of our own mental activity, which may be at the root of consciousness. In fact, a pretty good argument can be made for a “sixth sense” on this basis. My feeling is that if a sixth sense exists, it is one that looks “in” instead of “out” like the other five.

The examples I have used are absurdly simple ones, and I don’t mean to give the impression that the process is always so straightforward. It can become immensely complex, but no matter how many variations on the theme you find, it’s still the same basic process.

Up to this point I haven’t said anything very controversial. I think most philosophers would largely agree with what I’ve stated so far. But there is a big split in philosophy and we are rapidly approaching that point. So, if you will look again at Exhibit A, you will note I have drawn a heavy line between the characteristics of analytic statements and the characteristics of synthetic statements. Philosophers generally lumped together as empiricists say there is no crossing that line. Synthetic statements cannot be knowable a priori, (in your head without reference to the world). Philosophers usually gathered under the general heading of rationalists claim at least one such statement and they may claim more. They go on to claim that starting with such a statement as a given and using pure reason (deductive logic), all of reality can be derived.

Such statements are usually termed metaphysical (beyond physical) or supernatural which conveniently releases them from the constraints Mother Nature places on the rest of us. Probably the classic metaphysical statement of all time is: “God exists.” So much controversy has swirled around just this one metaphysical statement that the various positions have their own labels. There are theists, atheists and agnostics.

A theist is a rationalist who claims a priori knowledge that the statement “God exists” is true. An atheist is also a rationalist, but claims knowledge that the statement is false. All true empiricists are agnostic. They claim knowledge is not possible concerning the truth or falsehood of this statement, or any metaphysical statement, since such statements do not lend themselves to observation and verification by the senses. An agnostic would maintain that such statements are matters of faith, not knowledge.

Agnosticism is really a much broader category than most people realize. For instance, one can have faith that “God exists” is true and still be an agnostic. Or you can believe the statement is false and be an agnostic. Only the claim of knowledge will move you out of the agnostic category one way or the other.

Other metaphysical statements abound and usually concern the existence of things such as souls, spirits, gods of all kinds, large and small, ghosts, poltergeist, goblins, etc. In fact, the field is wide open. You can dream up your own. All you have to do is claim knowledge that they exist, but that they do not lend themselves to sense observation. Talk about free enterprise! This is really an unregulated industry!

The trouble with human beings is we have very active imaginations and, although this can be entertaining and useful when properly channeled, it often runs wild and tempts us to create answers where voids in our knowledge exist. These answers form the dogmas that differ from one religion to the next. They differ because they are not based on common experience of the senses. Whole wars have been fought and unspeakable atrocities committed in the name of these differences. As a species, and as individuals, we need to discipline ourselves to reserve judgment where voids in our knowledge exist. We need to learn to say, “I don’t know” without feeling inadequate. We must be patient.

In conclusion: all objective truths or “facts” are simply matters of high probability and all knowledge about the physical nature of the Universe is of this nature.

“I think that in discussions of physical problems we ought

to begin not from the authority of scriptural passages, but

from sense-experiences and necessary demonstrations…

Galileo Galilei

Searching for Truth

I was raised a Christian of Protestant persuasion. After a number of years of Sunday school my parents sent me to membership classes which I attended faithfully and was confirmed by a concluding communion service as a full-fledged member.

I remember that during the membership classes I was troubled by a reoccurring thought that I couldn’t seem to get out of my head. I would sit there listening to the instructor (the minister’s wife) tell us the “right” way to believe, and I would imagine a similar class taking place on the other side of the world where a Hindu instructor was telling little candidate Hindus the “right” way to believe. I was sure that these two “right” ways were probably different enough that they couldn’t both be “right.” I suppose some people would simply pass off this difficulty by saying that we are right because we are who we are (naturally superior) and they are wrong because they are who they are. Somehow I could never bring myself to use that argument, not even in my own private thoughts.

There are, of course, many “right” ways to believe, and many of them are contradictory or mutually exclusive. When I raised this problem in the membership class I was told “what they believe is right for them, and what we believe is right for us.” This didn’t make me feel much better. It made truth entirely subjective, and it seemed to me that a great word like “truth” deserved better than that. I could understand how a certain amount of cultural relativity must be necessary concerning the laws needed to govern a civilized society, but when it came to defining the ultimate nature of reality I was convinced there could be only one right answer.

None of my fellow students seemed to be bothered by this problem, or if they were, they kept it to themselves. I went ahead and completed the indoctrination to please my parents, but it became clear to me at that time that I would be unable to swallow any predigested orthodoxy in its entirety. I would have to decide for myself those tenets which I would believe and those which I would reject. And where I couldn’t decide, I would just have to reserve judgment for a while. It was going to be a long process. So I became eclectic in my beliefs, picking and choosing as I gained experience and hoped that someday I would be able to see a pattern that would make things easier.

Right from the first I discovered it was not easy to be eclectic. You had to think. Plus, it took some fortitude to say “I don’t know,” when everyone else was buying the canned answer. But after a while, I grew interested in the problem, and actively pursued my own personal research. I noticed that most religions seemed to have two major parts. There was the system of morals and ethics which they advocated as proper behavior, and there were the reasons why. The latter usually included an explanation of the ultimate nature of reality and some incentives, both positive and negative, for proper behavior.

I observed that, on a very basic level, proper behavior was defined in a very similar manner by most of the religions I looked into, but the reasons were quite different. Since there didn’t seem to be much argument about what proper behavior meant, I initially took to carefully examining their various ultimate realities. Here I was confronted with a bewildering cast of supernatural characters playing their roles on various metaphysical stages. I was lost and confused. I was sure there was only one truth concerning the ultimate nature of reality, but which one was it? I remained in a state of suspended judgment for quite some time. There just didn’t seem to be any good way of coming to a decision. I also doubted myself, and was bothered by a nagging sense of guilt. Had I not disobeyed my parents and teachers? What if they were right? If they were, then the Christian God, who was included in my doubts, would surely know and disapprove of my thoughts. But no punishment seemed to be forthcoming. Perhaps I would “catch Hell” in the end.

Eventually, as I obtained a better historical perspective, I thought I detected an evolutionary trend in the concept of supernatural beings. It appeared to me the more primitive a people, the more specific was the spiritual content of their world as they perceived it. And, by contrast, the more advanced a civilization was, the more general was the concept of spiritual beings.

Early or primitive people saw a spiritual presence in almost everything that occupied their environment. There were tree spirits, animal spirits, river spirits, and so on. More advanced cultures such as the classical Greeks and Romans tended to lump things together by categories and put a god in charge of everything relating to that category. There was Neptune for the sea, Mars for war, Diana for the hunt, etc. In both cases the spirits or gods were used to explain actions or circumstances which people could not explain in any other way. As time progressed and people became more sophisticated, they began to realize that most things in nature were interrelated and one phenomenon could often be explained in terms of another. At this point monotheism came into being. If most things were related, you really didn’t need all those gods. One would do nicely.

Some things remained the same, however. The single god was still used to explain things that could not be explained in any other way. “It’s God’s will.” People imagined God as a being who consciously designed, built, and operated the universe, much as humans designed, built, and operated machines. The interrelatedness of nature reminded people of a very complex machine.

Along came the scientific revolution. Humans beings became much more knowledgeable about the nature of things and much better at explaining the world they experienced. Evolution could explain earth’s diversity of life in terms that made the story of creation seem quaint and old fashioned. The concept of God became more abstract. Perhaps God wasn’t a being after all. Maybe people had been designing God in their own image instead of the other way around. Maybe God was something more fundamental that lay at the very root of the existing universe, a basic unknown force of some kind.

“Unknown” is the key word in the last sentence. It struck me that God always began in people’s minds where knowledge left off. As knowledge advanced, God retreated. However, the more we knew, the more we realized we didn’t know. God was not diminished, but simply became more abstract. The retreat was in the sense that God was less immediate to our everyday lives.

This was about the state of my personal thinking on the subject of religion at the time I entered college in 1956. It remained at this status quo for about two years while I struggled through the demanding first half of an engineering curriculum at Oregon State University. Finally, in my junior year, engineering students were allowed to take a few electives. I immediately opted for philosophy and art much to the disgust of my engineering counselor. I took a course entitled An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis taught by Professor Peter Anton. I found that course utterly fascinating, and still count it as the course that influenced me the most during my university career. I hung on Professor Anton’s every carefully chosen word. That was quite a contrast to my engineering courses where staying awake was usually my problem. Strangely enough, I didn’t do well from the standpoint of grades. Totally inept when it came to writing an essay exam, I was used to engineering exams which were problem solving, true or false, multiple choice, etc.

I considered changing my major to philosophy at that point, but I was well into my junior year and in those days it also would have meant a change of universities since Oregon State did not have a full-fledged philosophy department. Eventually, I decided to “stick it out” with engineering, but my heart wasn’t in it and my mind was elsewhere.

What did I learn in Professor Anton’s class? As the course title indicates, it was an introductory course. We got a little syntax, a little semantics, some logic, but my favorite was epistemology, the study of knowledge. As I think back on the subject many years later, I am pleasantly surprised at how much I retained. I am sure Professor Anton would be surprised too since I only got a “C” in the course.

If pressed to do so, Professor Anton classified himself as a “logical empiricist” and as he led us through the distinctions between inductive and deductive logic, a priori and posteriori knowledge, synthetic and analytic statements, I suddenly realized that this was the philosophical underpinning of science and engineering. This was the general theory from which the Scientific Method is derived. How short-sighted of my counselor to try and steer me away from this course! It was the foundation on which their various disciples were built and fundamental to their existence. I was amazed by the irony. It made a huge impression on me. It also made my industrial engineering curriculum a little more bearable because I began to see it was “applied philosophy.”

To this day, I do not understand why the subject of epistemology is not more broadly taught. Especially for students of technical subjects, but really for everyone. I have encountered high powered scientists with doctorate degrees who do not understand in the most fundamental way what they are doing, and I think that is a shame.

How do you know what you know? This, to me, seems like the most fundamental of all philosophical questions. If you can’t pin down the nature and basis of your knowledge then everything else you think you understand is really on a pretty shaky footing. What is the mechanism or procedure by which human beings accumulate knowledge? Are there some things that are beyond knowledge (not knowable) and how do you know that? The name of the field that addresses these questions is epistemology.

I find this a difficult subject to write about. It is not that the subject is elusive, as when writing about art, the distinctions and definitions are fairly clear. The problem is that I started out with the intent of setting down my views in an interesting and readable way, and I can’t see how to deal with this subject in that manner. This probably represents a limitation on my part, but I know from the experience of trying to explain it, that it is not a subject that a lot of people find fascinating. I do, but then I’m a little. . . On the other hand, I consider the subject to be of critical importance. It is the trusty foundation which has served me well now for many years.

The Philosophical Roots of Science will probably require a little study. At it’s core is what I learned from Professor Anton almost fifty years ago. It has been on the back burner of my mind ever since. Occasionally I have brought it forward, stirred it, tasted it, added a little seasoning, and put it back on low heat to bubble away. But now I think it’s time to serve it up. I hope it’s not overcooked.

R. L. Mason

On the road in Alaska, 1986

Revised 2009

Art by Definition

It seems to be my nature to try to reduce things to their essence. I do this unconsciously. Concepts bubble away in my mind at low temperature until some quintessential expression surfaces which satisfies my need. One of the most difficult that I have ever struggled with is the concept of art. I have made my living within the art field for a considerable amount of time, and I still feel very cautious about trying to define art, or who is an artist and who is not.

Part of my difficulty comes from my training in science and engineering. These are objective fields whereas art is subjective. In engineering, if something works … it’s right, if it doesn’t work …. it’s wrong. Degrees of right or wrong do exist, but that is the general thrust. In art there are so many individual points of view it is quite difficult to make generalized statements. Nevertheless I am compelled to try.

Art is what artists do, and conversely, an artist is a person who does art. I know that sounds so obvious that it’s silly, but if you accept this, at least we have narrowed the field semantically. Here is what my Webster’s New Collegiate says about art:

1.a: skill in performance acquired by experience, study, or observation.

b: human ingenuity in adapting natural things to man’s use.

and Webster says an artist is:

1.a: one who professes and practices an art in which conception and

execution are governed by imagination and taste. b: a person skilled in one of the fine arts.

I rather like those, particularly the emphasis on skill and the line about “ingenuity in adapting natural things to man’s use.” But before going any further I should say that I am referring to fine art as opposed to commercial art. I’ll explore that distinction after this lament:

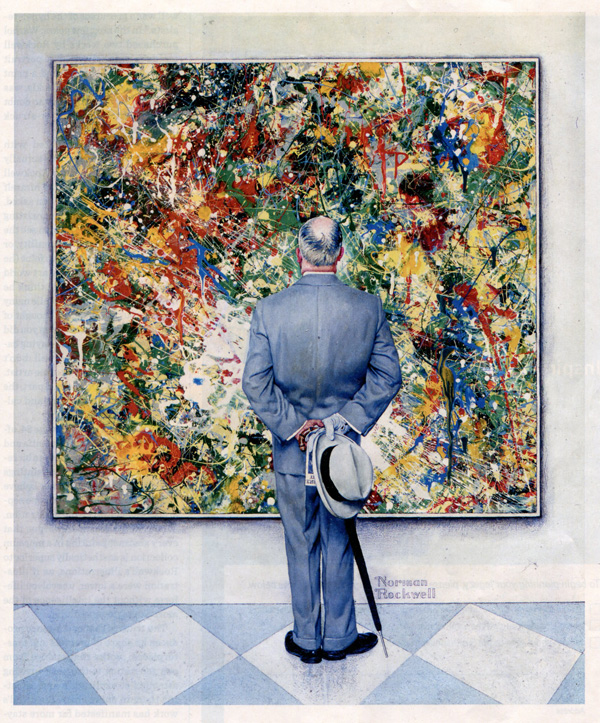

A trend in art schools and among the art intelligencia (professors, critics, curators, etc.) seems to urge an ever expanding definition of art. Increasingly diverse endeavors are included under this heading. In competitions where members of this group are jurors (and that is more often than not) they usually hang ribbons by works which are unusual or unexpected and therefore original, all other qualities being secondary. Craftsmanship and beauty are frequently sacrificed on this cross of originality. In their eagerness to comply, the budding young art students often create ugly, poorly executed, but unusual pieces. In fact, it often appears that what makes them so unusual is their aesthetic shortcomings. Beauty is derided as “pretty,” and craftsmanship is mere “technique” or “facility.”

Proceeding in this manner the art intelligencia has produced a definition of fine art of such breadth that it encompasses almost everything. This reductio ad absurdum (is that an oxymoron?) is diluting the whole concept of fine art. In some cases one can no longer distinguish art from a random happening, and the artist is indistinguishable from anybody else. I have also heard art defined as a process of self discovery. Again, a very broad definition, and probably true, but you might as well be speaking of life itself. Surely we can be more specific than that.

One school of thought maintains that in order for a work to be significant art, it should make a statement usually something of socially redeeming importance. I agree that art can do this, but I believe it is of secondary importance. By way of contrast, James A. McNeil Whistler, an undisputedly fine artist, composed and delivered what he called his “Ten O’clock Lecture,” which dealt at length with the subject at hand. In it he spoke of art as:

“She [art] is a goddess of dainty thought — reticent of habit, abjuring

all obtrusiveness, proposing in no way to better others.”

Instead of “statement,” I like the word “content.” A statement is best made with words in a left brained medium like writing with its capacity to be specific and express sequential development. Art makes use of images and is, therefore, right brained in nature. Art is much better for conveying or producing an immediate impression. This, in part, accounts for the difficulty of writing a comprehensive definition of art in the first place. Because of its very nature, art is easier to recognize than define.

Art critics reviewing shows try to express with words what is best done with the brush. The resulting verbal contortions are often amusing. Of course, I could be accused of attempting to do the same thing, in a general way, as I accuse the critics of doing in particular. This defining art is a tricky business. However, I will put forth my candidate definitions, but first something about purpose and skill that I believe bear on the definition.

A second school of thought is in some ways just the opposite of the “make a statement” people. The proponents maintain that an artist should never set out to do anything in particular, that serendipity should reign supreme. One should simply begin and let the vagaries of the medium suggest a path to be followed. Works accomplished in this manner have energy, vitality, and are expressive, displaying a spontaneity which is the true measure of the artist. Further, those who begin work with an intended purpose are not really producing fine art, but instead are making illustrations, and are consequently lowered in status to illustrators.

This approach, carried to its logical conclusion, produced the abstract expressionists. I do not deny the validity of this approach as I have seen fine works accomplished in this manner. Works of the abstract expressionists can be decorative and pleasing to the eye, but often lack content. One of the largest markets for such work is the decoration of corporate and government offices. Because of its lack of content, it can be hung in the lobby of their headquarters without running the risk of offending anyone.

The trouble with being guided primarily by serendipity is it minimizes forethought. On this planet forethought is a uniquely human quality. Products of forethought, or planning, have characteristics which are easily recognizable. A chimpanzee can paint with energy and vitality. His efforts might even be called expressive, but only a human being can create a work of art in which another human being can ascertain a reasoned thought process or purpose.

Many works by abstract expressionists have the look of something found in nature. “Organic” is a term often used to describe them. I have seen slices from a moss agate or enlargements of photos taken through a microscope that could easily pass for a painting by an abstract expressionist. To the extent that a work of art resembles a random happening I am bothered by the lack of human content. I like art which speaks of the artist, art that reflects the humanity of its creator. Art is, after all, something that is done by human beings.

How many times have you heard a person standing in front of a large abstract painting say, “Oh, I could do that.” The usual retort is, “Maybe, but you didn’t.”

Unfortunately, a large degree of truth exists in such spontaneous reactions. The abstract expressionist loses his uniqueness as an artist and human being. His skill is not readily apparent. In essence, the medium becomes the artist and the artist simply an applicator and that is something that most people can do.

Human endeavors are recognizable as human endeavors because they display intelligent purpose. When an archeologist goes into the field to search for evidence of ancient human presence, how does he know when he has found it? He knows when he sees the randomness of natural elements ordered in some way to serve a purpose. The particular purpose may not be apparent, it may be symbolic, but the fact that a purpose was involved is easily recognizable. The archeologist suspects that human beings were present, even if only several stones are found in a straight line. When gazing at the night sky the human eye is quickly drawn to Orion’s Belt for the same reason. Three stars of equal magnitude, evenly spaced, in a straight line, it looks like the work of the human mind. Consequently, I see no harm in approaching a work of art with purpose. Serendipity is a valuable tool and it will add spontaneity to a piece, but it should not allow the medium to overrule the artist.

At this point I should separate art from other human activity. Art, fine art, tends to be symbolic rather than functional. It often tends to represent something rather than be something. It attempts to capture an essence. But that is not quite enough. It must also do this so as to create a harmony of its various aspects and elements. I suspect this relates to the structure of the human brain. Certain patterns and combinations seem to fit our brains better than others. A tune is more pleasing than a kitten on the keys.

If all artists are human beings, are all human beings artists? I think not. Since all human characteristics are distributed on a bell curve or normal distribution, some human beings will be better at creating the “fit” than others and they are the artists. It’s all a matter of degree, of course, and it’s entirely possible that no human is completely devoid of this ability, but the difference from one end of the spectrum to the other is pronounced enough to deserve a word to describe those with the ability, and that word is “artist.”

The skill or talent of an artist is most apparent when he or she displays control over the medium. When, through innate ability and/or experience, artists are capable of causing the medium to serve their purpose, it will be readily apparent to the observer. Works produced in this manner will have content. They will say what the artist intended, and they will say something about the artist.

Control over the medium can be carried too far, of course, resulting in a stiff or slick look, but most of the shortcomings I see are in the other direction. After all, mastering composition, perspective, light, form, and color takes time and effort, not to mention the handling characteristics of a particular medium. Many people would like to “leap frog” the whole process, but as an art teacher friend of mine is fond of saying, “the only way out is through.”

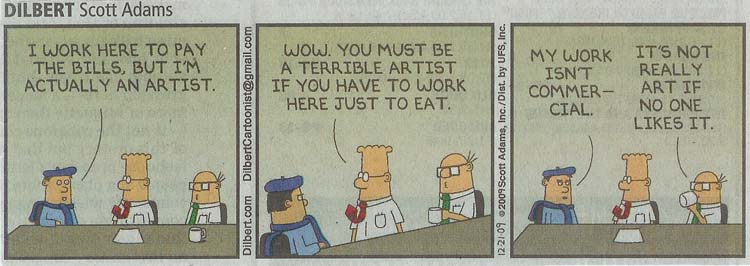

As for difference between fine art and commercial art, the distinction is fairly clear. When the artist selects the image, medium and content, then he or she is at least attempting fine art. How fine it is will depend on the artist. When someone else pays the artist to produce what they want, the result is commercial art. As usual, a considerable gray area exists. For example, where do you place a portrait artist? The art intelligencia will often stretch the term “commercial” to include any work an artist undertakes with an eye toward its eventual sale. They feel that the selection by the artist of a popular subject matter or style sacrifices the all important originality. By scorning popular subject matter and style as “commercial” and thus removing popularity with the art buying public as a measure of merit, the art intelligencia is able to control the nature of art that will eventually receive critical acclaim.

Pity the plight of the fine art student. Perhaps in high school they discover that they enjoy creating in art classes, and maybe an innate ability reveals itself. Consequently, they decide to become a fine arts major in college. There they encounter the avante garde of the art world who direct their efforts toward the unusual and bizarre. Upon graduation, they are focused on what is probably the smallest segment of the art market, which, in total, is too small for them all anyway. And whereas all of their fellow students were prepared by the university to survive financially in their chosen field, just the reverse is true for them. Plenty of exceptions to this scenario exist, of course, but it is a common enough story. The lucky will find work in related fields as art teachers, curators, critics, etc., where, if they persist, they may eventually become part of the art intelligencia and thus perpetuate the cycle. I once read in an editorial of a national fine arts magazine that less than one percent of those formally trained in fine art actually make a living selling their work. It is something that I have never been able to accomplish.

I started this discourse with the intent of creating a comprehensive definition of art. Along the way, I realized the impossibility of that task and I spun off on a few tangents while developing a rationale, but now I feel the need to carry through. Here are my candidates for the great art definition competition:

Art is a skillful arrangement of elements assembled by a human being to produce a symbolic essence of the human experience.

An artist is a human being who possesses the skill to arrange elements in an order that produces a symbolic essence of the human experience.

These are inadequate, I know, but they are the best I could do. . . . with words.

“The things we deal with in life are usually too complicated

to be represented by neat, compact expressions . . .”

“. . . in any case, one must not mistake defining things for

knowing what they are.”

Marvin Minsky

R.L. Mason

On the road in Alaska, 1986

Revised 2007

The Basic Law of Civilization

Most major religions of the world contain a system of morals and ethics, and many of them will claim that these rules were handed down from on high by their deity. The deity’s authority is therefore behind the rules and the deity or deities will mete out punishment or reward depending on the degree of adherence to the rules by the individual, group, or society. The deities, for the most part, are metaphysical syntheses beyond the reach of the five senses. They have no direct base of evidence in the physical world so they tend to be quite different from one religion to the next. However, if you toss all these religions in the air and let all their differences winnow away in the wind, are there any basic similarities that drop out, any kernels of truth? It seems to me there are.

When all the chaff is blown away, their systems of morals and ethics, at least on the very basic level, seem to be remarkably similar. Why is that? Could it be that all the various societies governed by all these various religions have some common problems dealing with life in the real world? And could it be that this set of common problems has generated a set of practical remedies which is necessarily very similar from society to society (“like conditions produce like results”)?

Well, if that is the case, then the systems of morals and ethics did not really come from a supernatural source. They were generated here on earth! It would appear, therefore, that civilization has been pretty much a bootstraps effort and its rules were not gifted upon us. We got them the old fashioned way. We learned them.

The Sun, beneficial as it is shining down upon us, did not provide for civilization. It provided the setting and climate in which life could begin and it sustains life, but what we do with life is up to us. We have to figure out how to get along, and all the other life forms must do the same. Civilization is an attempt to assure survival through cooperation.

The next question appears to be, what are the rules that comprise the code for living in a civilized society? The enabling legislation for civilization if you will. Can they be distilled to some essential expression which is succinct and easily recognizable as true? A number of philosophers have had a go at this, and I paraphrase three who are often cited below:

Immanuel Kant came up with what he called the Categorical Imperative:

You should always act in accordance with the principles which you desire to be universal.

John Stuart Mill blessed us with the Doctrine of Utilitarianism:

That course of action is most just that does the most good for the greatest number of people.

But, the one I like best, the one that says it the clearest for me is often attributed to Jesus Christ but probably predates him. It’s the good old-fashioned Golden Rule:

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

I have also heard this referred to as Reciprocal Altruism which sounds a little less folksy. Reciprocal Altruism, however, implies that your actions toward others should always be positive, and yes, that would be included under the Golden Rule. But simply refraining from negative actions towards others would also be included under the Golden Rule and yet would seem to be excluded from Reciprocal Altruism. Those who expound on Reciprocal Altruism suggest a evolutionary or genetic basis. I would argue, however, that the Golden Rule is derived from experience. It’s memes not genes.

I note that all of these are based entirely on practical considerations and have nothing whatsoever to do with any deity. It would appear, therefore, it is possible to be a good and moral person in the eyes of civilized society without subscribing to any of the orthodox religions. Bigots may deny you, but society in general will not be able to fault your actions if they are always in accordance with, for instance, the Golden Rule.

I would like to raise this Rule to the position of eminence which I think it deserves, free it from the doldrums of Sunday School dogma. I would do this by renaming it. I propose that it should be known as the Basic Law of Civilization. However, I will refer to it from here forward as the Rule.

You cannot have a civilized society unless the members of that society, individually and collectively are, for the most part, guided in their thoughts and actions by the Rule. If it is not expressed explicitly by a society then it is at least observed implicitly and when observance of the Rule is neglected to some extent, then civilization will break down to the same extent. In fact, there is a relationship between the Rule and civilization which is “hand in glove.” One almost defines the shape of the other. If a civilization springs into existence from the whole cloth of some previous jungle state then the Rule is bound to be operating to some degree, and the greater the adherence, the higher the civilization. That’s my personal view at any rate.

Is civilization worthwhile?

Professing adherence to the Rule assumes that the result, namely civilization, is worthwhile. Is it? In some ways this is a more difficult question to answer than how to bring it about and maintain it. In 1986 as I traveled through Alaska, I read John McPhee’s book, Coming Into the Country, in which he describes the lives of the “river people” living along the Yukon River between Eagle and Circle. Many of these people were trying to get away from it all, to get back to nature, to basics. However, none of them are able to go completely native. Even the natives were no longer capable of that, because to do without civilization entirely is an extremely difficult way of life. You must become almost an animal. I met some of these river people and they had managed at least for a period of time to distance themselves from civilized society, but they still enjoyed the products of civilization. They had their rifles, outboard motors, chain saws, and they bought bulk foods processed in some distant factory to supplement their hunting.

Humans are not well equipped to lead an animal existence. We do not have sharp teeth and claws like a cat, and we cannot run as fast. Humans must rely on their intellect and the tools we develop are reflections of that intellect. We are tool using animals.

If you are attempting to live off the land, then a large portion of your mental and physical effort must be directed to simply surviving. Just obtaining your subsistence occupies the majority of your time. This can be very rewarding, but you don’t have time to stop and build a rifle even if you were capable. A rifle is a complex product of other tools that must be built first.

The products of civilization make life a lot easier. Hence, civilization makes life a lot easier. When you are part of the warp and woof of civilization you can afford the time to think about things other than surviving. You can take a trip, write a book, create a work of art, or anything else that gives you pleasure or satisfies your curiosity.

I have read that during the siege of Moscow by Napoleon, and later during the siege of Leningrad by Nazi Germany, men of great learning, philosophers, musicians, and scientists, were reduced entirely to thoughts of survival. Civilization was breaking down and every waking moment was spent trying to figure out how to provide subsistence for themselves and their families.

I think it is fair to conclude, therefore, that civilization is worthwhile, and even though distortions will always exist to some degree, the very mechanism that permits these distortions, namely freedom from the drudgery of survival, also provides for the best that the human race has to offer. Culture and the advancement of knowledge are enabled allowing us to better understand our place in the Universe. In short, since civilization makes life easier, it is in the best interest of each individual to insure that it continues, and that is the real reason for being a person of good moral character, someone who adheres to the Rule. It is simply intelligent, long-range self-interest.

Isn’t it strange that this reason for being a person of good moral character is so seldom taught? You always get those other reasons, the threat of punishment, or the promise of reward, either here on earth or in some life hereafter. As if we were all small children. It seems to me that even a child could understand the practical reason, if we just took the trouble to explain it.

Civilization, to the extent that it exists today, has been hard won over a long period of time, but is probably more fragile than most people realize. We are still “proving up” here on the home star homestead. One way of looking at the history of the human race is as a progression of learning to live together in successively larger and larger organizations. First there were families. Then there were tribes and clans, followed by feudal states. Nations arose and eventually gathered together into alliances or blocks of nations, but attempts at gathering us all together, such as the League of Nations and the United Nations, may have been premature for our current state. I hope not.

If the Rule is the Basic Law of Civilization, then it applies to intelligent entities of any kind, and the degree of their adherence could be considered an indicator of their wisdom. For instance, it should apply to legal entities such as nations in their dealings with each other. Unfortunately, one does not have to look long or hard in this sphere to find violations of the Rule. Some of the most influential nations, the ones that should be pointing the way, keep slipping back to jungle mores such as “might makes right.” I’m afraid the world will not become a civilized society of nations until we choose as our leaders human beings who understand the Rule is The Basic Law of Civilization.

R.L. Mason

Mendocino, California

circa 2004

Sex and/or Violence

Sex and violence, sex and violence, sex and violence, it has become a kind of media mantra linking these two over and over again. They are uttered in the same breath, in the same sentence, and tarred with the same brush of scorn, they are the twin evils of modern society.

I have always been somewhat puzzled by this marriage for they seem to me a very odd couple. It is hard to defend violence. There is almost always a victim, someone is injured, coerced, or at worst, loses their life. About the only acknowledged justification for violence is self defense. A point which is unbelievably stretched in the popular entertainment media. It is also found in some sporting events, of course, but that could be termed consensual violence and doesn’t usually carry any stigma. Other than these two, I think it would be fair to say that violence is almost always wrong and deserves its lowly reputation.

Sex, on the other hand, even if it is only a poor imitation, is at least based on an act of love. A prominent philosopher once said that the only prerequisites for sex should be mutual inclination and considerations of health and manners. When these are met not only is there no victim, but there can be an exchange of pleasure which is quite intense. On top of that sex is a necessity of life. We cannot continue to exist without it. If one could wave a wand and suddenly eliminate all violence from human society it certainly would not be missed. Civilization would be much improved. If, however, you waved a wand and eliminated sex, not only would you have done away with a very positive experience, you would have done away with us as well.

I realize there are instances when the two are physically linked as in the case of rape. But rape is primarily violence. It’s not what the rapist is after that is evil, its the way he goes about getting it. Some will say that what the rapist is really after is power through physical domination. Maybe so, but that’s still violence. If you force someone to do anything they don’t wish to do, that is violence. If you coerce them by the threat of violence to themselves or to someone they care about, that falls into the same category. Coercion should also be suspected if one party is below the age of consent.

If you force a person to eat ice cream who does not wish to do so, and this repeated often enough, I suppose the victim might develop an extreme distaste for ice cream. One might even come to link ice cream and violence in one’s mind. Ice cream and violence, ice cream and violence, a new mantra? Even so, its obvious that the ice cream was never at fault, it was violence all along.

Money sometimes suffers from a similar problem. Surely you have heard money described as the root of all evil. Money is, of course, simply a morally neutral medium of exchange, but so many immoral, unethical, and illegal means are used to obtain money that it is sometimes viewed as evil itself. If a person wants money and robs a bank to get it, its not the money that was at fault, its the method that was used to get it.

The image of sex suffers from another cause, and that is the way it is often poorly portrayed in the popular media. Although this may now be changing, in the past this frequently took the form of an unrealistic power disparity between the sexes. The males are represented as strong, authoritarian, often wealthy, and the females are young nymphets with idealized good looks and not much mental capacity. And whereas the male is cast as accomplished with worldly goals, the female (especially in commercials) is shown as a person whose “be all and end all” is to attract a man or men. I think this qualifies as a very subtle form of coercion even when a relationship appears to be consensual.

A further problem for sex comes from the attitude of the worlds established religions. Most cast aspersions on sex in some way. In Christianity sex is often associated with the concept of original sin. What practical considerations would be at the root of this attitude and cause such a negative view to become fixed in religious dogma? Possibly it was the health risks associated with promiscuity. Maybe it was the threat of excessive procreation. Perhaps it wasn’t so much a practical consideration as a genetic one. Genetic survival is a very strong drive in all living things. If opportunities to pass on ones genes were limited for some reason then there would be motivation to restrict sex in such a way as to insure that ones own genes were successful and not those of a rival. Any of the above could be the subject of extensive speculation and research, but they all have been considerably mitigated in modern human society.

From a purely scientific viewpoint, biologists point out it wasn’t until the advent of sex that the great diversity of life on earth became possible. Prior to that, life replicated through dividing to produce clones. Sex allows the mixing and combining of different genetic materials to produce a vast array of evolutionary developments.

In conclusion, therefore, I vote the we grant sex a divorce from violence. Let her be free of this abusive relationship and assume her proper place among the delights of our society. Rather than be scorned she should be celebrated in art, literature, and music.

Mother Nature made sex pleasing so we would not neglect to partake.

R. L. Mason

Mendocino, Cailfornia

Circa 2005

Cousinhood

The average person has first cousins, second cousins, third cousins, and so on. Furthermore, there are cousins once removed, cousins twice removed, cousins thrice removed, etc. If you are like me, once you get past second cousins or cousins once removed you have no idea who these people are, or were. But even if you have long since lost track, where the relationship actually exists there is, or was, a personality to fill each slot.

It’s a fascinating exercise to ponder the number of cousins one might have. Exact calculations are difficult because everyone’s situation is different, but if you could come up with a uniform scenario then maybe . . . Suppose every marriage was perfect and lasted a lifetime during which each couple always had exactly two children at exactly age twenty (fraternal twins) and only by their spouse. Furthermore, suppose the couples are always exactly the same age and everybody lives to be exactly 75 years old. In other words, these are the kind of improbable people that government programs are tailored to fit. With all the irregularities removed, calculating cousinhood for this uniform population becomes a possibility. I attempted this and came up with a set of numbers organized in the form of a matrix with the cousin number (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.) across the top and the number of times removed (once, twice, thrice, etc.) down the side. The full matrix is included as Exhibit A for those who like to gaze at such things. I’ll just summarize a few interesting points here for your amusement. The total number of cousins gets quite large very quickly as the numbers increase in value. By the time we reach two digits (10th cousin 10 times removed) we find over a billion cousins in just that slot, and the cumulative number of cousins up to that level is substantially larger. It’s interesting to note these figures would only carry us back about two hundred years (about as far as United States history goes). Remember also that these figures are for two children per couple. The actual historical average in the U.S. is higher, and in many other countries the averages are significantly higher. On the other hand, there will always be cousins that stay single, childless couples, and those who die young.

Each individual will have over one million cousins about their same age, and someone could easily have as many as 20 million cousins alive at any one time out to the 10th cousin number. At the time that George H. W. Bush was elected President of the United States, Burke’s Peerage in Britain determined that Bush was the 13th cousin twice removed from Queen Elizabeth, according to Harold Brooks-Baker, publishing director. Actually, this is not surprising since by extrapolating a little on my cousin matrix, I calculate that the Queen would have 268,435,456 cousins in that same slot. Almost anybody of British extraction could make a similar claim.

Now, here’s something fun to consider. If you are married and you and your spouse have similar ethnic backgrounds, the probability that you are married to a fairly close (10th or less) cousin is pretty good. If your spouse is of a different race, you will still be cousins but at a higher number. At some level, everyone there is, or ever was, is your cousin. Cousinhood includes even those who happen to hold specialized titles such as father, mother, son, daughter, sister, brother, aunt, uncle, etc., and variations on those obtained by adding “grands” and “greats.” How can that be? Well, let me explain . . . If your spouse is really your cousin at some number, then your children are your cousins at the same number, but once removed, and vice versa. For example, if first cousins marry (that is legal in some states) then their children are also their first cousins once removed. And since children of first cousins are second cousins to each other, then the children of this couple are second cousins as well as brother and sister. All the other special relationships can be explained as cousins in a similar way.

Are you still with me? Now let’s really go to “fast backward.” Imagine a meter before you like the odometer in your car. This meter shows the “COUSIN LEVEL,” meaning both the cousin number and the times removed. The reading gets rapidly larger. On the right, the last rotor whirls about as fast as it can go and still be readable. The spread of cousinhood resulting from the rising cousin level is reflected in the following events. Human beings join the chimps and apes in cousinhood . . . then orangutans and lemurs. Next we join the other higher mammals! The meter is picking up speed. The first rotor is just a blur and the second is too! Cousinhood descends through lower mammals, joins birds and warm blooded dinosaurs, then reptiles. Now the meter is really singing! Vertebrates join non-vertebrates. Listen to that meter scream! The animal kingdom joins the vegetable kingdom; lichen, slime mold, protozoa, bacteria . . . and then . . . CLANK! . . . the meter comes to an abrupt halt at some immense number. Life is cousinhood. To the best of our knowledge, life has begun only once on this planet. We are all cousins under the Sun.

R. L. Mason

On the road in Alaska

1986

Teaching By Example

I no longer consider myself a Christian, having gone onto what I believe to be a larger view of things; but many of their teachings are well founded. In particular, I recall the method they chose to spread the word, and that was to teach by example. In their view, Christ led an exemplary life, teaching us by his example, and we were obligated to carry on in that same vein.

A few sects and denominations today choose more aggressive methods of proselytizing. There are those that ring your doorbell and push their literature at you, and those that trumpet loudly from various media pedestals. But my guess is that they alienate many for every one they convert. Proceeding to quietly do right by your fellow human beings and then letting the chips fall where they may seems to me a more effective way to gain respect, admiration, and possibly adherents.

In the over two hundred year history of our nation, all of our presidents have been men and at least, claimed to be Christians. It is doubtful that they could have been elected without those two designations. The day will come when that is no longer the case, but as of this writing it has yet to arrive. As Christians, many of them were exposed to, and understood, the advantages of teaching by example. They realized that not only is this a good rule of conduct on an interpersonal level for spreading a religious philosophy, but it is also effective on an international level for spreading a political philosophy.

The United States is a form of democracy and we believe that democracies in general are a highly beneficial form of government. We recommend them, but we have not, for the most part, aggressively pushed them on others. Today there are approximately 125 democracies in the world, of which we are the oldest, and I believe this is in no small part due to our example. We have provided an environment for our citizens that has liberty, opportunity, and a fair amount of justice. And although we are not perfect, our systems are continually improved through public debate and citizen participation. As a result, we have become a wealthy and powerful nation.

Other peoples of other nations have had a long period to observe our progress and witness our success. Many have decided that we are on the right track and worthy of imitation. Admittedly this is a slow process, but the progress has been steady and always the numbers increase. Sometimes this has been accomplished by revolution and sometimes by gradual reforms, but when complete, the people of the nation involved take pride in having brought about this change on their own, and rightly so.

In the few instances where a democracy has been imposed upon another nation, it was a result of defending ourselves or our allies against aggression from those nations. The aggressor nations were defeated and a democracy was installed. The defeated nations were in no position to object, having brought about the conflict in the first place. However, they came to appreciate their new form of government and are now among the most peace-loving nations on earth.

This brings up another benefit characteristic of democratic nations. They are usually nations that place a high value on peace. On becoming a democracy, they join a community of like-minded nations. Trade and cultural exchanges ensue and this provides a firm and stable basis for prosperity. By and large, democracies do not start wars. Wars are almost always started by nations with authoritarian governments.

The early Christians were relatively powerless. The only means they had at their disposal for spreading the word were persuasion and teaching by example. Using these methods, they were able to expand the movement rapidly throughout the Western world. Later, when Christianity became the established religion of powerful states, other methods were tried. In particular the crusades spring to mind. Powerful western nations attempted to impose Christianity on other people through military force. Their record of success was not impressive. Desirable ends do not justify undesirable means.

We need to keep this in mind when we are tempted to speed up the process of democratization in the world by imposing it where it does not currently exist. It will be more readily accepted and more highly valued where people bring about the change themselves. In the long run, nothing changes in society in a fundamental way unless individual minds change first. Circumstances can get out of balance in the short run when a government tries to force change from the top down, but if officials get too far out of line, they are voted out of office or there is a revolution.

Fundamental change is a bottom up process and converts are made one at a time. People must be convinced, and one of the best ways to do that is to show them a good example. At times this will mean we must endure what seems to be the interminable reign of some despot, but with the recent advances in worldwide communication, time is very much on our side. And while we wait, we can concentrate on becoming an even better example. This will not go unnoticed.

Categories

- THE GALLERY

- Uncle Rob's Art

- 3D Works (stills) I

- 3D Works (stills) II

- 3D Works (stills) III

- 3D Works (video)

- Design & Abstract I

- Design & Abstract II

- Design & Abstract III

- Figurative Works I

- Figurative Works II

- Landscapes I

- Landscapes II

- Largest Art Project

- Nautical and Marine Images (video)

- Nautical and Marine Images I

- Nautical and Marine Images II

- Nautical and Marine Images III

- Nautical and Marine Images IV

- Portraits

- Still Life Images

- Stump Hollow Photo Essay I

- Stump Hollow Photo Essay II

- Uncle Rob's Mendocino Shop

- The Five Sense Series

- Irene's Creations

- Works by Don Mason

- Works by Don Mason II

- Works by Joseph de Borde

- Painting by Albert Robbins

- Art by Leslie Masters Villani

- Paintings by Nellie Harriet Parker

- The Art of Bee Yearian

- Works by Evie Wilson

- Uncle Rob's Art

- SCHOONER MOON BOOKS

- SEA STORIES

- ONE DOZEN AND TWO ESSAYS

- Cousinhood

- Art by Definition

- Cake Mixed Economy

- Marriage Anyone?

- Sex and/or Violence

- Searching for Truth

- The Philosophical Roots of Science

- Stepping Stones and Stumbling Blocks

- On Being Good

- Teaching By Example

- The Basic Law of Civilization

- Where Goeth Evil?

- A Modern Empircal "Religion"

- Knowledge as Wealth

- PAPERS AND ARTICLES

- FAMILY STORIES

- BOOK REVIEWS

Archive

- December 2021

- October 2020

- June 2020

- September 2019

- July 2017

- March 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- February 2015

- January 2015

- February 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- August 2013

- June 2013

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- November 2011

- September 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008